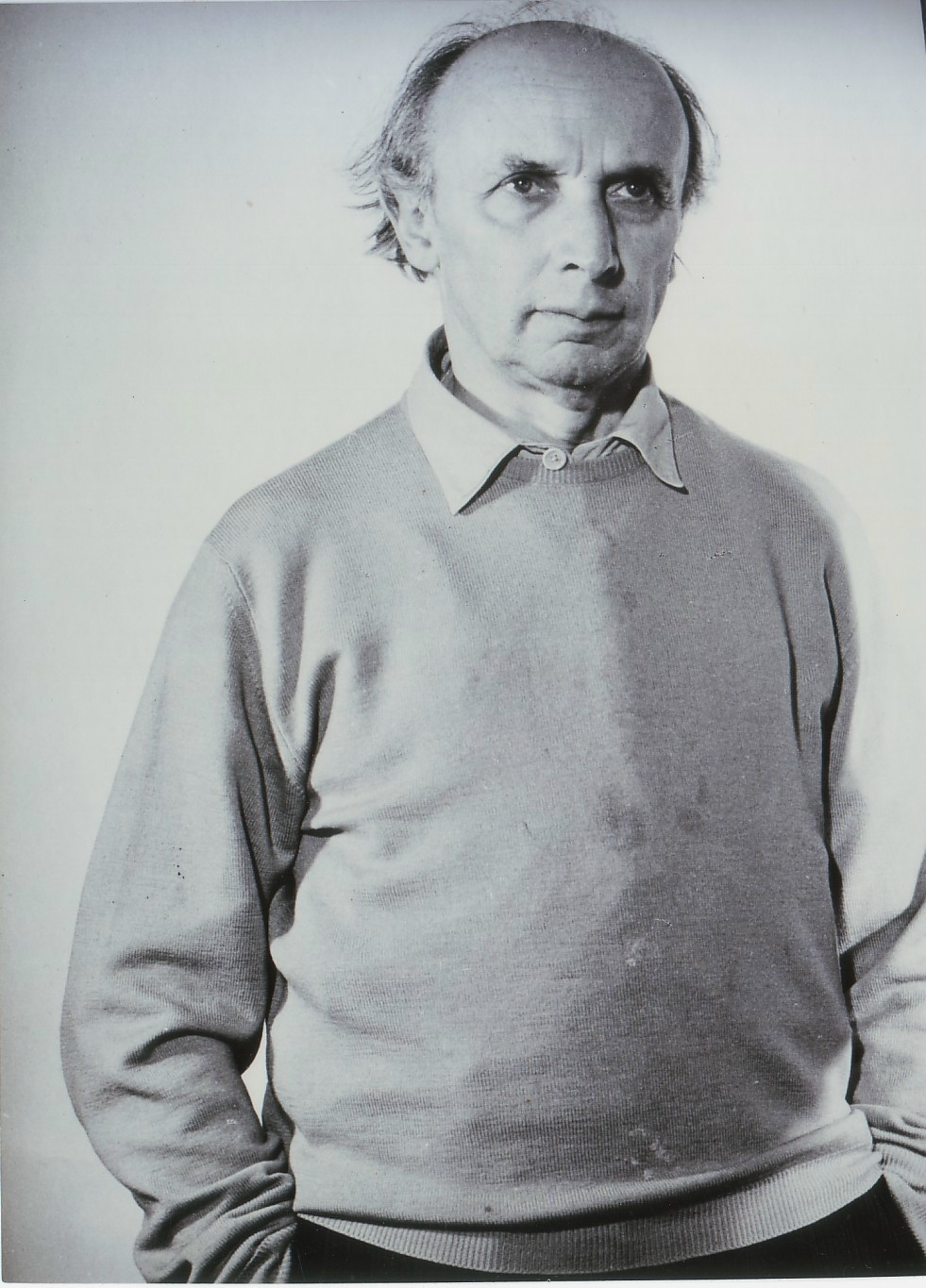

Imre Hofbauer was born on 5 November 1905 in Mitrovica — then in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and now part of Kosovo — and grew up in the north, in the region of Tatabanya. According to his mother, little Imre “could paint before he could speak”.

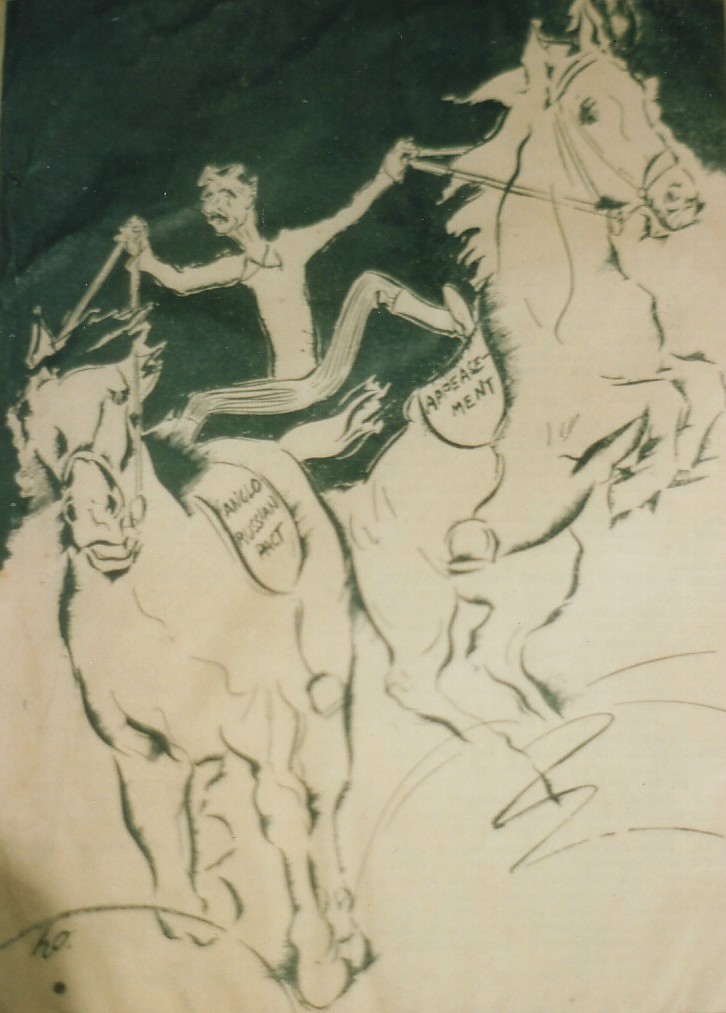

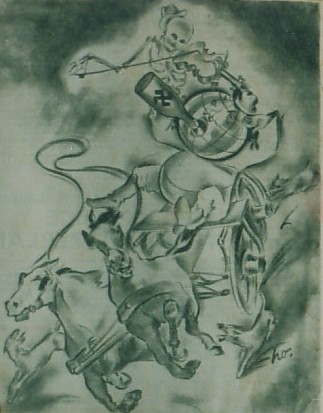

At the beginning of the 1930s, he went to Prague where he studied architecture until 1933. In order to pay for his tuition, he became a cartoonist for several Czech newspapers. Simplicissmuss, the famous German satirical weekly, also published some of his work.

Afterwards, he left Prague and went back to Budapest where he worked for the most popular dailies such as Az zest (The Evening) and Budapesti Hirlap (The Budapest Mail). In 1935, he became the manager of The Athenaeum, a rather important publisher in Central Europe in those days.

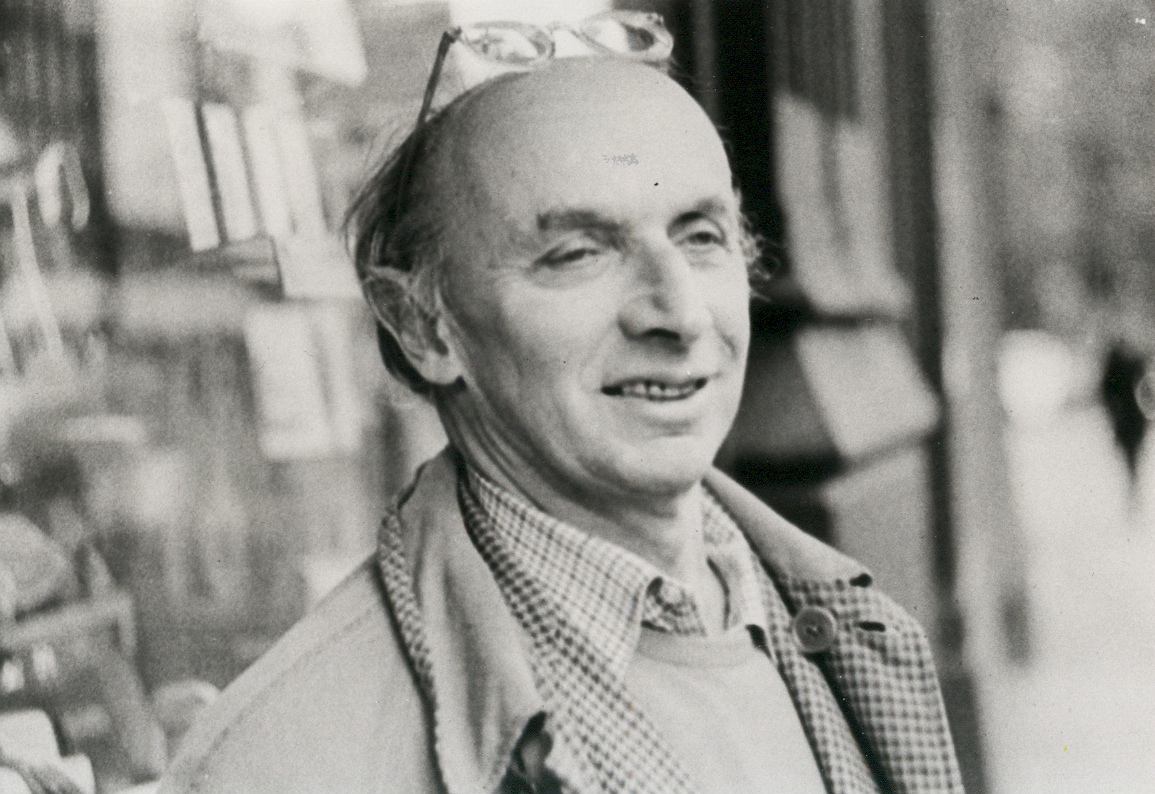

His life became increasingly imperiled because of his satirical cartoons against Hitler’s regime. Escaping the Nazi persecution, he moved to London in 1936, where the newspapers he worked for had sent him for a report, and where his close cousin Alejandro Pollak had been living for a few years. Seduced by the atmosphere of freedom that reigned in the British capital, he never left it, except for some short stays in France, Switzerland and Spain. Frightened by the spectre of impending Nazi aggression against Eastern Europe, his mother – who had remained in Hungary – committed suicide. He never returned to his homeland. Not even in 1964, for his first personal exhibition.

A few years after his arrival in London, World War II broke out.

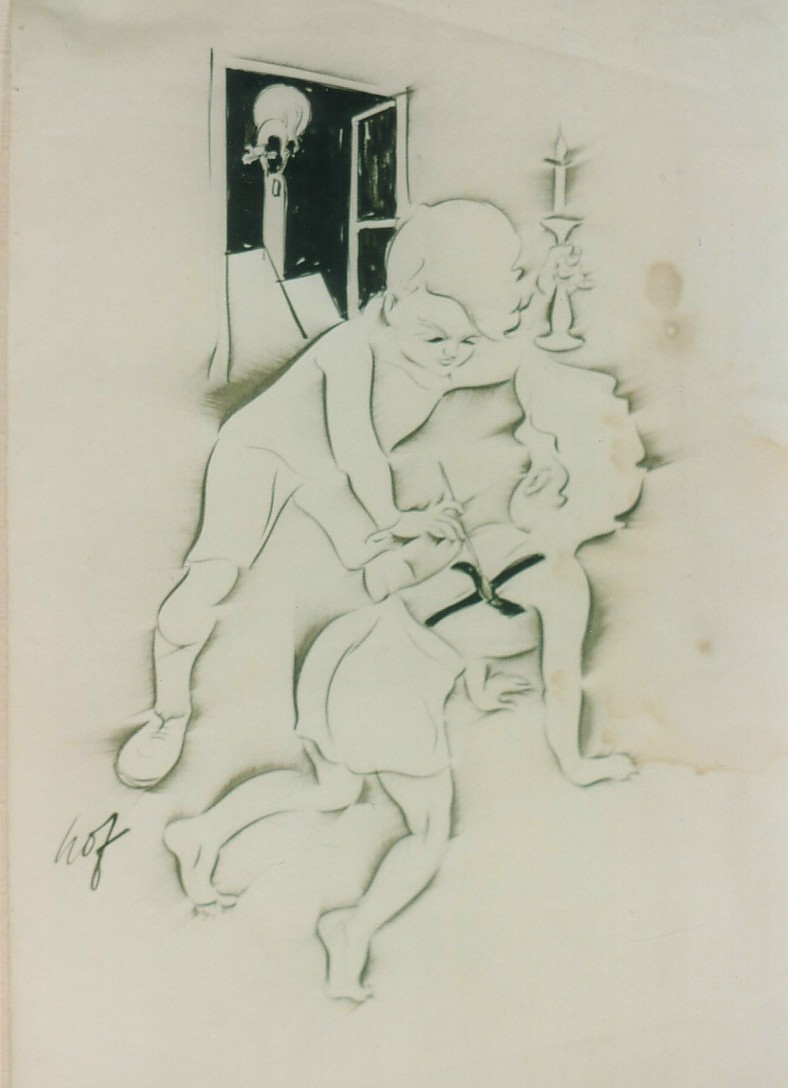

“Hof” — as his close friends used to call him — volunteered for the London fire brigade and help the victims of the German air raids. The horrors he witnessed during his service inspired some of his most powerful works, which were sketched in pencil on scraps of paper and published in 1942 as the book Calvary, under the pseudonym “Peregrine”.

It was his way of denouncing the atrocities of the Third Reich’s crimes, his way of defending human dignity. Despite his predilection for solitude, Hofbauer spent his life defending the helpless and denouncing injustice. Born Jewish, he received a Catholic education, and adopted the New Testament maxim of “love thy neighbour.”

When the war ended, Hof had made London his home, and most of his work was devoted to the city, its buildings, its inhabitants, its everyday life. In addition to the numerous paintings he made on this subject, he published The Other London (1948), a volume of drawings. Eighteen years later, he also collaborated with Richard Church on London, Flower of Cities All (1966). In these two books, his architect’s eye mingled with his humanist view and depicted thrilling portraits of London, with oil paint, Indian ink, and more importantly with watercolour, his favourite technique because of its transparency. Above all, he wanted his paintings to capture and bear witness to an elusive period: London in the second half of the 20th century.

Although Imre Hofbauer’s painting is steeped in London aesthetic, Hungary is also a big part of his work. Several motifs referred to memories of his childhood and youth in Hungary. In addition to the hundreds of paintings he made, several of the books he wrote and/or illustrated reveal this nostalgia: Bababukra (1947), in which he gives flamboyant descriptions of his country, and My Little Englishman (1945), a quasi autobiographic tale.

Moreover, two of the recurring topics in Hofbauer’s work are fishermen and miners, another allusion to his background: his father, a sailor, died at sea when Hofbauer was just a child, and Tatabanya, the town where he grew up, was a mining region.

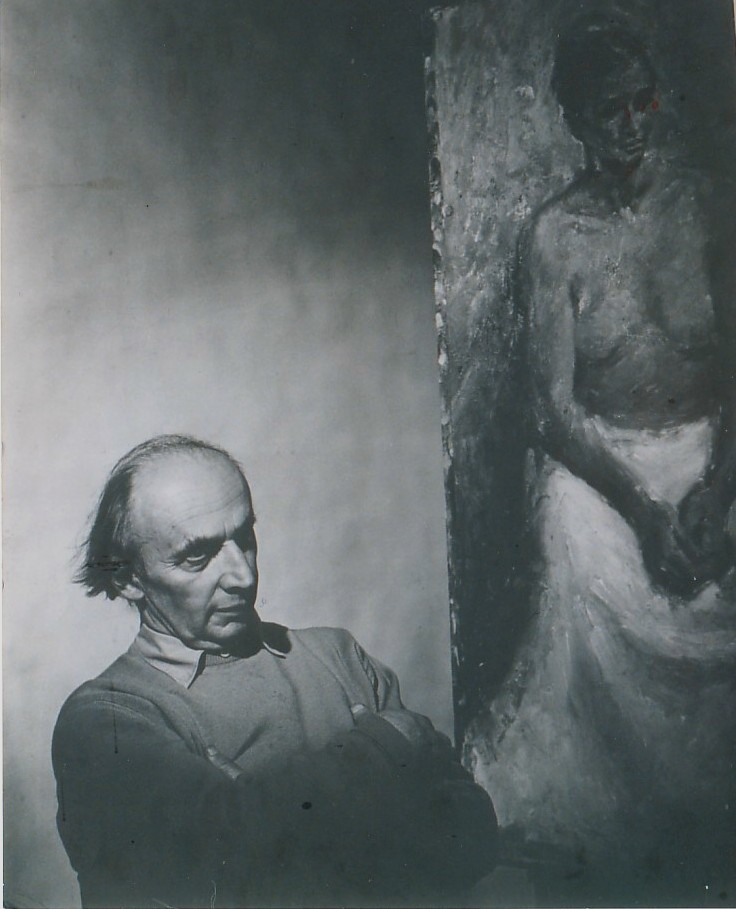

As for the artists that inspired Hofbauer, we know that among his contemporaries, he particularly admired George Grosz (he even edited a book on Grosz’s work) and Jules Pascin. However, he remained unimpressed by recent trends like Surrealism, Post-Modernism, Cubism, or Dadaism. He steered clear from all artistic currents: he wanted to be himself, detached from fashions and schools, and was continually exploring new paths. In one of the scrapbooks found in his studio after he died, he wrote: “The unspoken ideal to draw well, realistically; drawing for drawing’s sake, as did the masters of bygone days…” He invented a special technique with translucent film material he fabricated by himself, and which allowed him to find varied and subtle shades. After his death, hundreds of proofs were found in his studio.

During the last three years of his life, Imre Hofbauer — who used to be very athletic — could no longer carry on with his usual lifestyle and was unable to finish several paintings and manuscripts that he had started. Hofbauer’s vision of art became dark and pessimistic during the last years of his life. Among his unfinished work, is the book On Teaching Art, an essay where he stated his personal views: “While speaking on the subject, I realize that it is harder to say than it seemed during the many years it has lived in me. So, let me state the important facet that most probably does not emerge till one spells it out: draughtmanship has shrunk.”

Imre Hofbauer died on January 5, 1989. He was 84.

Immediately, his deeply humanist work was scattered around the world, through Europe and the United States. He received eight international prizes. All his life, he advocated for art’s grandest vision, and all who knew him knew that he was his own harshest critic, both in his work and in his private life.

Slowly and quietly, he had painted voiceless souls and given birth to thousands of pieces of art, that can now be found in dozens of private collections worldwide.